Song: I know where I am going

Modern Saber Fencing by Zbigniew Borysiuk moves into

great depth about the sport of saber. It provides a discussion of fencing

history, electronic scoring, modern saber, fencing nutrition, research on

fencing, fencing talent, diagnostic tools, reaction, and information

processing. The book offers scientific knowledge of fencing and has been

reviewed by doctors and Olympic coaches to bring cutting edge information to the sport. It

is a great book for those who may want to take their fencing from recreation to

competition some day. It provides all of the basic information one needs to

move down that path.

There is an interesting chapter on fencing and

information processing. It discussed the concepts of stimulus detection,

differentiation, recognition and identification. Stimulus detection is the perceptual

moment when a stimulus occurs (i.e. opponent’s movement). Differentiation is the understanding of the

different types of stimulus (i.e. movement and location) Recognition affords

the opportunity to detect and differentiate with a coordinated learned activity

(i.e. the type of activity by opponent). At the highest level is identification that

once the specific action is recognized different types of activities can be used

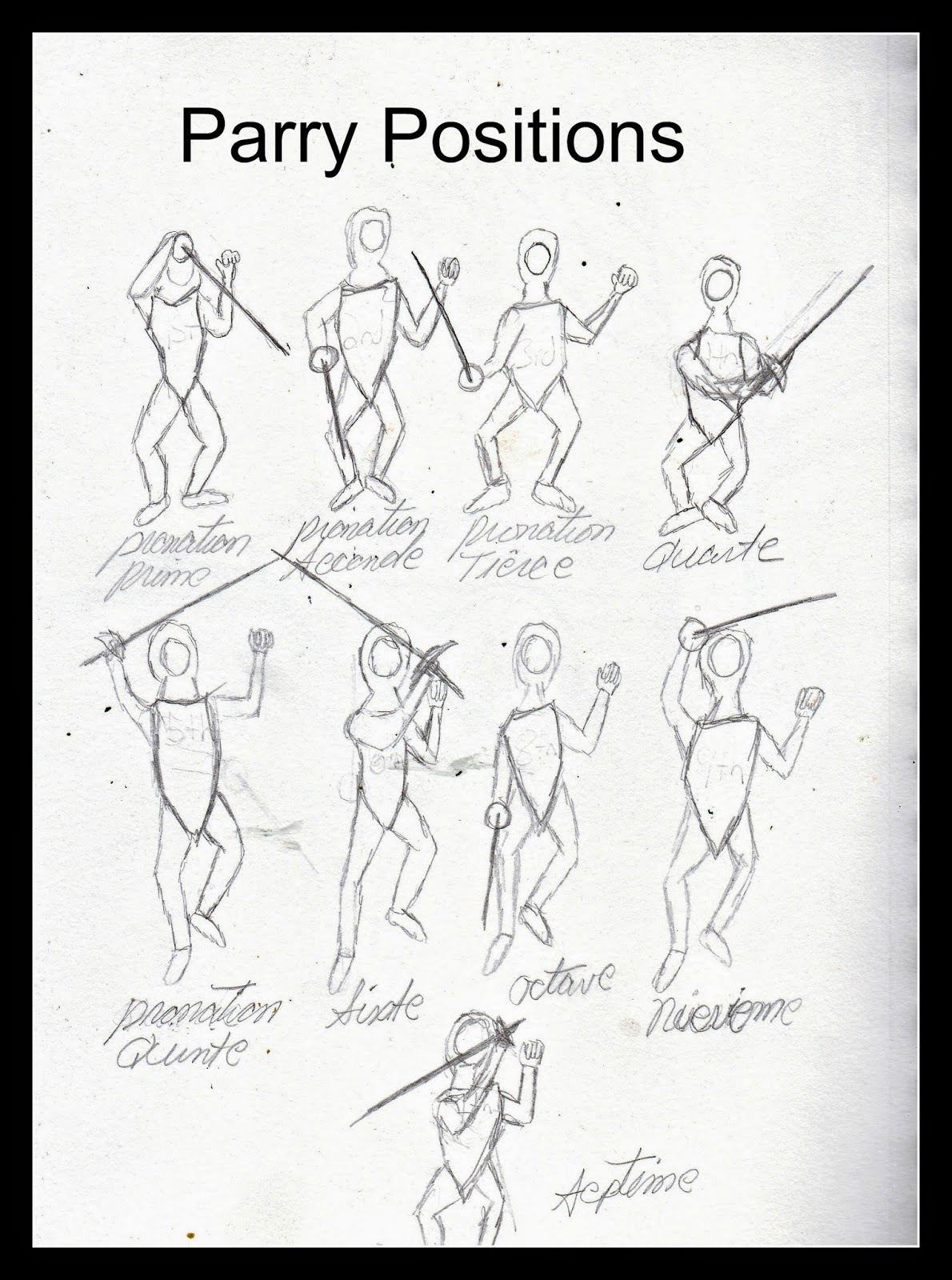

to respond (parry leads to counter parry and five possible alternative actions).

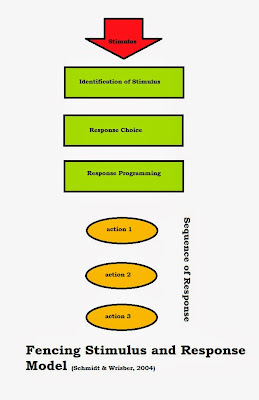

As stimuli move into one’s plane of perception it is

identified (see above) and then the player can choose a learned response. The

quality of the response is based upon the programming of training. At times the

player can choose a single or multiple responses. When a player can create a

complex chain of responses he/she is seen as more of a master of the game.

Success being in control of the game and ensuring you understand and have

responses to activities in multiple ways. The more learned and ingrained varieties of

movements, the better the player.

As stimuli move into one’s plane of perception it is

identified (see above) and then the player can choose a learned response. The

quality of the response is based upon the programming of training. At times the

player can choose a single or multiple responses. When a player can create a

complex chain of responses he/she is seen as more of a master of the game.

Success being in control of the game and ensuring you understand and have

responses to activities in multiple ways. The more learned and ingrained varieties of

movements, the better the player.

All responses from stimuli can be learned except

acoustic. This is why new players are wilder in the game but those that

understand the signals have more concise and less wieldy responses. A player

has begun to master the game when he/she can overcome automatic responses and

moves more closely into learned responses. These learned responses come from

thousands of hours of practice. Understanding movements and ensuring

proper form is necessary for future success when actions are ingrained.

Unlike some other sports, fencing is highly cardiovascular

,like running or swimming, and develops very refined sense of stimulus

detection. A single wrist movement or adjustment of body posture can tip off

the opponent to the next action. For example, while fencing last night the more

skilled player with 20+ years of experience could tell when I was going to

lunge. He was able to even point out how my front leg became tenser just before

the attack. He used his experience to wait until I was in a full movement and

then countered with a strike. Likewise, he noticed by the end of the first bout

that I had good reaction times and decided a defensive stance with coaxing my

actions worked best. This type of awareness cannot happen unless one has

watched and practiced many endless hours of fencing.

If you desire to know how the three bouts turned out

it was 5-0, 5-0, and 5-1. The single point I scored was from taking his advice,

falsely tensing my leg, making a small action forward, waiting for his counter,

and then striking him in the upper left shoulder. Sometimes you have to feel

good about the little victories when you are learning. It only worked once!

Borysiuk, Z. (2009). Modern saber fencing. NY: SKA SwordPlay Books ISBN

978-0-9789022-3-0