Time management is of concern to

most managers and employees that have some control of their daily schedules. It

is also a concern to executives and managers that want their employees to be

productive at work. Those employees who know how to effectively manage their

time appear to have an advantage over those who don’t. Research helps highlight

how successful employees are in finding appropriate strategies to put their

efforts to maximum use.

Successful completion of goals

and tasks requires employees to maintain the ability to schedule their time

appropriately and make the most effective use of their efforts. The success of

the business, as well as it managers, rely on strong and poor time management (Bahtijarevic,

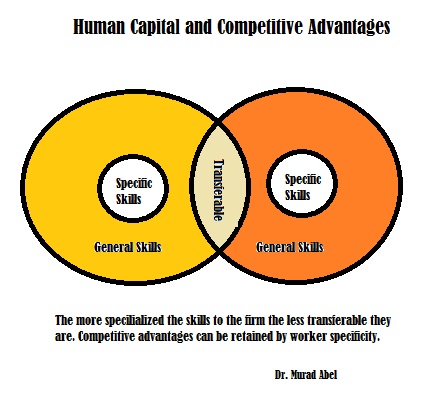

et. al., 2008). Time can be seen as a resource that when used effectively is a

competitive advantage to organizations when compared to those organizations the

ineffectively use time.

Successful time management can mean different things

to different people and should have a process. Time management requires the

ability to decide what should be accomplished, the importance of those tasks,

and the priority of these tasks (Lakein, 1973).

With an effective method employees are more knowledgeable of the

requirements each day and more focused in their efforts.

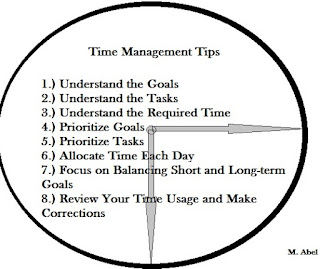

Effective time management requires a process that is

helpful in conceptualizing available time resources as allocated to the

organization. According to Macan et. al. it is necessary to 1.) set goals and

priorities; 2.) making lists; and 3.) have a preference for the organizations

needs (1990). Not having a preference

for the organization means that time will be used on more personal and less

constructive activities.

A study conducted by Mitrovic, et. al. (2013) helps

to understand time usage within a Serbian company and how businesses can more

effectively improve upon that time management. It aims to study the degree in

which employees effectively schedule their time and helps to define factors in this

effective time management. A total of

180 employees out of a possible 220 responded to the survey.

Results:

-Daily planning of the day’s tasks was best done

immediately after arriving at work. It is suggested that is a tallying of all

required tasks, their arrangement and then understanding the amount of time

each of them needs to be completed.

-56% of employees plan their schedules daily, 24% do

this irregularly, and 20% didn’t plan on a regular basis. This helps highlight

the use of time resources are not being effectively utilized.

-49% of employees know their most productive part of

the day, 22% do not know when their most productive time is and 29% are unsure

of when their most productive time is. Employees should understand when their

most productive times are and utilize this time effectively.

-70% of employees knew what the most important tasks

for tomorrow were, 12% didn’t know what the most important tasks for tomorrow

were and 17% were unsure. Employees should learn how to be more aware of

upcoming tasks and learn how to be proactive in their scheduling of time.

- 39% of employees did not update

their project plans, 27% of employees were not sure, and 34% updated their

project plans. Employees had more

difficulty managing their time on longer term projects.

The study helps highlight the

necessity of training employees to effectively use their time in order to

maximize time resources and human capital. The results indicate that

effectively managing time requires the use of lists of tasks that are

prioritized and have appropriate time allocated to each of these tasks. The

best time of the day to prioritize tasks is early in the morning. The longer

and more tasks the project requires the less ability employees have to plan

their time accordingly.

Bahtijarevic, et. al (2008). Siivremeni

menadzment. Zagreb, Skolska knjiga

Lakein, A. (1973). How to get control of your time and your

life. NY: New American Library.

Macan, et. al. (1990). College

students time management: correlations with academic performance and stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82.

Mitrovic, S., Bozidar, L, Knoja,

V. & Nesic, A. (2013). Employee time management: a case study from Serbia. Metalurgia International, 18 (1).

Bookmark with Your Social Network

Bookmark with Your Social Network